Moving Fast With CDOT

How we improved a critical intersection in two-ish months for less than $10,000.

What if our state and city agencies could solve problems in weeks or months rather than years and for tens of thousands of taxpayer dollars rather than millions?

We got to talking with CDOT about this and decided to collaborate on a project to try the modern entrepreneurial toolkit in a state DOT setting. We organized a Design Lab, a process in which stakeholders and experts get together in a room and over a couple hours hammer out a testable hypothesis to take into the real world and try to solve a problem.

We convened the group at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science on January 30th and by the first week of April, just over two months later, we had a project on the ground for less than $10,000.

Here’s how we did it.

Before the Design Lab, we established four objectives:

We also created a set of “design constraints”:

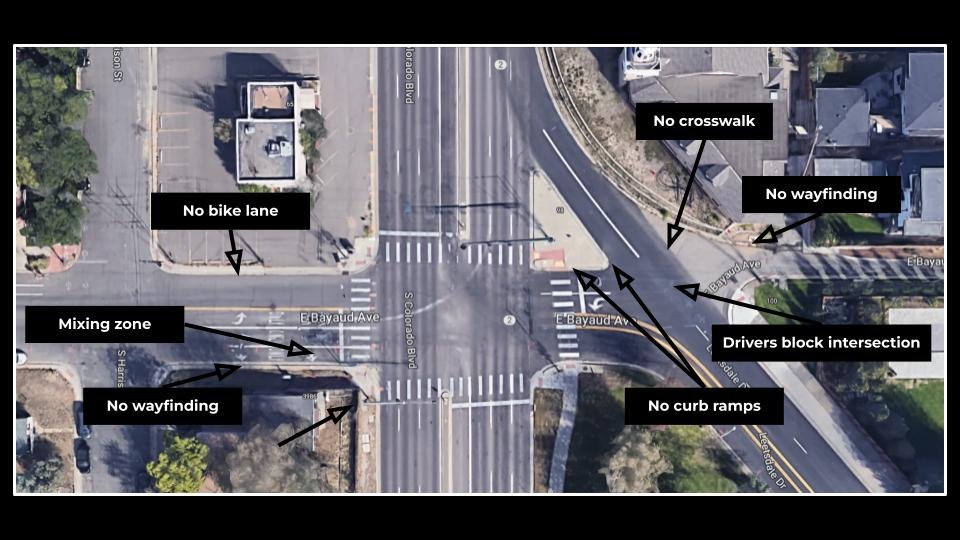

We chose to work on the tricky intersection at Leetsdale, Colorado, and Bayaud, which is an important connection point on the Denver Bike Map.

We outlined a set of problems for cyclists and pedestrians, most notably that there is no crosswalk on Leetsdale and when drivers stop at the new traffic signal on Leetsdale they block the intersection at Bayaud.

We left the Design Lab with a testable hypothesis: that temporarily closing the Leetsdale slip lane and having drivers turn north on Colorado Blvd at the signal at Bayaud would make the Leetsdale crossing safer for pedestrians and cyclists.

The CDOT team did the heavy lifting to navigate a set of internal processes that don’t typically work this way. And by early April we had our changes on the ground.

The design changed substantially between the Design Lab and construction, which is a big opportunity for improvement in the future. But most importantly, we ran a modern innovation process and met the design constraints: it cost less than $10,000, we got it done more or less within the allotted time frame, it lasted more than one week, and we measured the impact of our work.

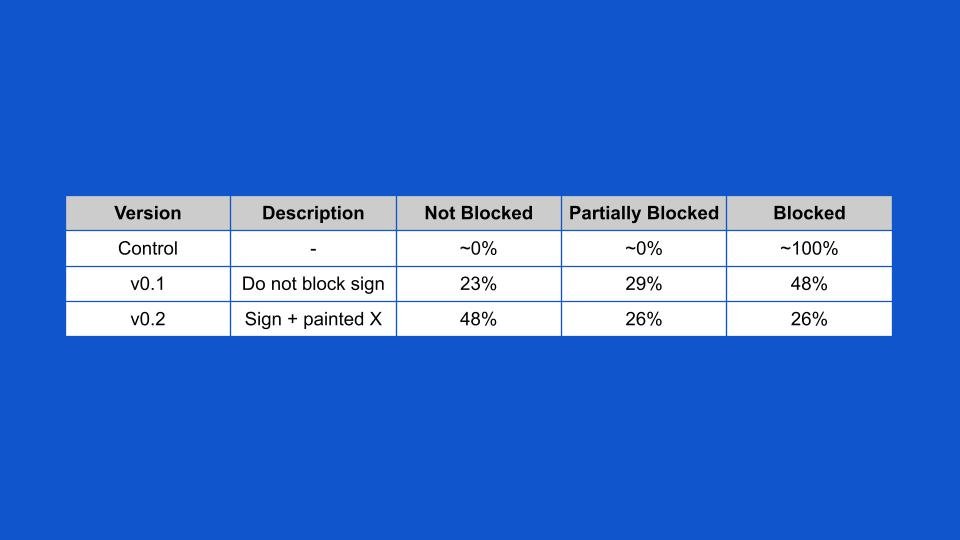

The change is a combination of a “Do Not Block Intersection” sign and a painted (technically, thermoplastic) X on the ground. Neighbors are enthusiastically calling it “The Crisscross.”

Design constraint #4 underscores the point that we don’t want to just make stuff; we want to produce results for people. We sat in Burns Park and counted the number of times the intersection was blocked before the treatment, with the sign only, and with the sign and X combination.

Each incremental change increased the frequency with which the intersection was unblocked.

To be clear, we haven’t totally solved the problem. Our data collection before and after could be more rigorous. And critically, the design changes after the Design Lab didn’t adhere to the objectives, meaning we didn’t improve the intersection adequately for pedestrians and cyclists.

Even so, this is a beachhead for how to work in a more innovative fashion. To make it happen, the CDOT team moved mountains internally. We got something done. And it produced a real outcome.

Shouts out to the CDOT team who pushed the project through to completion; DOTI staff who participated in the Design Lab and supported the project throughout, Bike Streets volunteers who brought lawn chairs to Burns Park and counted cars, participants from CDPHE, MBAC, City Council, DRCOG, and the DMNS for providing the Design Lab space.